Subscribe to The Model Health Show:

TMHS 305: The Science of Flavor & The Dorito Effect with Mark Schatzker

It’s no secret that food-based illnesses have become deeply ingrained in our culture. From the obesity epidemic to an uptick in food addiction, it’s clear that somewhere along the way we’ve lost touch with how to form healthy relationships with food.

Unlike many other health problems, finding a solution to these issues isn’t clear. Traditional medical solutions aren’t applicable due to food’s basic function—we need it to survive. Food is something we all have to interact with on a regular basis.

Mark Schatzker has extensively studied and written about the link between food and behavior, including how traditional knowledge has overlooked an important piece of the puzzle—flavor. On today’s show, he’s sharing the fascinating science behind the production of flavor, and how modern food is designed to get us hooked. We’ll talk about how to hack the system, and how you can get back to your roots in order to find balance between flavorful foods and nutrition.

In this episode you’ll discover:

- How our food’s nutritional quality has become more diluted over time.

- The intuitive eating habits of cattle (and how it relates to humans!)

- How production of crops like corn has changed over the last few decades.

- The incredible link between flavor and nutrition.

- What reverse evolution is, and how it works on both humans and plants.

- The science behind why supermarket tomatoes taste so bland.

- What brain scans indicate about food addiction.

- Why sugar and flavor are a dangerous combination.

- Which two senses contribute to deliciousness.

- The definition of retronasal olfaction and how it affects our taste.

- Why your taste seems to change when you have a cold.

- What we can learn from babies’ intuitive senses.

- The three rules of flavor that you need to know.

- How flavor compounds are connected to pleasure.

- The two ingredients on a nutrition label that you should avoid.

- What we can learn from healthier, leaner populations.

Items mentioned in this episode include:

- Onnit.com/Model _ Get your optimal health & performance supplements at 10% off!

- Foursigmatic.com/model _ Get 15% off your daily health elixirs and coffee!

- The Dorito Effect by Mark Schatzker

- Steak by Mark Schatzker

- The History of Sugar: Sex, Drugs, and Entertainment – Episode 222

- Connect with Mark Twitter / Facebook / Instagram

Thank you so much for checking out this episode of The Model Health Show. If you haven’t done so already, please take a minute and leave a quick rating and review of the show on Apple Podcast by clicking on the link below. It will help us to keep delivering life-changing information for you every week!

Transcript:

Shawn Stevenson: Welcome to The Model Health Show. This is fitness and nutrition expert, Shawn Stevenson, and I'm so grateful for you tuning in with me today. Listen, food is one of the most important and intricate things in our lives. You know, this is one of those things where we just can't get around it. It's something that we're going to interact with on a consistent basis. And funny enough, it can also provide a lot of complications, especially in our world today. You know, food has become kind of the new frontier of problems, alright? Food has changed, and we haven't really discussed why that is. We haven't really taken a deep dive into what happened with food. Because the way that we evolved, the food that we have access to today is very different. Alright? And our guest wrote an incredible book. This book is going to blow your mind. 'The Dorito Effect.' Alright? And I've got a funny little story personally about Doritos, alright? Of course this is like a top snack food growing up. Listen, this is what I would do. I would go to 7-Eleven. You know, 7-Eleven is always there for you. It's always open. I'd go over to the chili and cheese pumps, instead of using the chips they give you, the little tortilla, the little tortilla chips, I'd get a bag of Doritos, open the bag, pump the chili and cheese into the bag, shake it up? Yeah, that's right. That's what I'd do. Okay that's called gas and blast, really what that is. Eventually it would literally cause me physical pain later, and I just- I tried to outsmart the process of eating this fake food by like, "I'll just get a white soda." That's what my mother would say, "Get a white soda." How about I just not eat the food that's hurting me in the first place? But this is some of the stuff that funny enough is talked about in this book in regard to like even animals having this intelligence to know what to eat, and how all of this change took place where we have access to all these different flavors that never even existed before in, for example, a Dorito. Right? So it's really, really fascinating stuff coming up today. So I want you to keep this in mind. Food is not just food, it's not just unsophisticated inert stuff that you eat. Food literally speaks a language that your cells have to translate, and some language is beautiful and well-articulated, and some language is straight up gibberish. But your cells still have to try to figure out a way to make sense of and decode for your body, alright? And today we're going to talk about the utterly fascinating properties of food that can help us to better understand cravings, addictions, obesity, and many other food-related situations prevalent in our world today. Before we do that, one of my favorite things in the world, something I have on a daily basis, is an extract concentration from coconut oil. It's MCT oil, medium-chain triglycerides. And there's so much benefit that we're seeing now in the data. So one study found that MCT oil has a thermogenic effect on the body and increasing your ability and positively altering your metabolism. So increasing your body's ability to metabolize energy at a higher rate. MCTs are also absorbed more easily, and just say we're eating- we'll just use the example with the Doritos, right? The bag of Doritos with the chili and cheese mixed in. When I eat that, it's a language. My body has to convert that into energy, right? ATP is kind of the energy currency of the human body, and that translation process is probably going to be pretty arduous. I'm probably going to end up losing money in that conversion, alright? MCTs work differently because they kind of bypass the normal process of digestion and can essentially go right to cells and provide energy, which is pretty cool. Another thing, they've been found to support your gut environment - so your microbiome - especially since they had been found to have the capacity to combat harmful bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Alright? Getting the bad guys out, alright? I love MCT oil, but specifically emulsified MCT oil. So it's like a coffee creamer, so for your hot tees and coffees, you can add this MCT oil in, in its emulsified form to give it a nice kind of creamy butteryness, alright? And I get this from Onnit, so head over to www.Onnit.com/model, that's www.Onnit.com/model and you're going to get 10% off all of their different MCT oils and emulsified MCT oil as well. Alright? So pop over there, check them out. I literally use it every single day. I love, love, love, love the emulsified MCT oils, alright? So check it out, and on that note, let's get to the iTunes review of the week. ITunes Review: Another five-star review titled, 'Turning Sixty-One In Florida, Vicky,' by VickyS. 'I'm a nurse, case manager, wife, mom, and grandmother. My husband and I listen to your podcast while working out, in the car, or on the beach. I'm living the life you describe, and your messages along with top motivators help me reinforce what sometimes can be isolating. It is so nice to have you in our corner, and we are in yours. Thanks so much.' Shawn Stevenson: Vicky, that's incredible. Thank you so much for taking this time to share that, and you're sixty-one years young, and I'm just so happy for you, and thank you for making me a part of your life. Everybody, thank you for popping over to Apple Podcasts / iTunes and leaving a review for the show. It means everything, alright? So if you've yet to do so, the show has been valuable in your life, do it. Head over, leave a review. Alright? I appreciate it so much. On that note, let's get to our special guest and topic of the day. Our guest today is Mark Schatzker and he's the author of the phenomenal book, 'The Dorito Effect.' His award-winning journalism has appeared in the New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Best American Travel Writing. He has also appeared frequently on television and is a radio columnist for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He lives in Toronto with his wife and three children, and I'd like to welcome to The Model Health Show, my guest, Mark Schatzker. How are you doing today, man? Mark Schatzker: I'm doing great, thank you for having me. Shawn Stevenson: Totally my pleasure. Totally my pleasure. Your book, phenomenal, phenomenal book. Mark Schatzker: Thank you so much. It was a labor of love, but there was a lot of labor, as you can imagine. Shawn Stevenson: Oh yeah, for sure. I want to talk about this actually, just kind of take a step back, and I want to know what sparked your interest. You know, you're a journalist, you're somebody who's a writer. What sparked your interest into studying food? Mark Schatzker: I like eating food, and this all really started as I was like a travel food writer. It really started, right after I graduated from university, I went to Chile to visit my brother who was working there. We went out to the beach one weekend and we brought some steak, and it was mind-blowing steak. It was steak from Argentina, and it was the kind of steak you put a morsel in your mouth and you're just like, "Oh my God, what just happened? That was the best steak I've ever had." So I asked what I thought was a simple question, which was why did that steak taste so good? And it took me like ten years to answer. It's a really complex question, it turns out. It resulted in my first book which was called, 'Steak: One Man's Search For the World's Tastiest Piece of Beef,' and that was really just a search for delicious steak. But then you start to ask these deeper questions like what is deliciousness and why does food taste good? Why do humans eat meat? Are we supposed to eat meat? Aren't we supposed to eat meat? If we're not supposed to, why does it taste so good? But then even I started to get interested in cattle themselves, because I spent a lot of time with farmers and ranchers, and they would see things like- I'd go and visit a ranch, and the rancher would say, "Well you know, those cows over there are mama cows, and they're over in the field with lots of legumes, clover, and alfalfa, and they're eating that stuff because they're pregnant and they need the protein. But over in that field, those are steers, and they're laying on fat so they're not so much interested in protein as carbs, and that's what they're going for." And you sort of scratch your head and you think, "How do they know? They don't know what carbs are, they don't read Men's Health. Shawn Stevenson: Right. Mark Schatzker: And yet somehow they're eating the food that they should be eating. And that led me to this very interesting domain of science where they talk about things like flavor feedback, and how animals are guided by an intuitive sense of what they need. But basically, those cows were eating what they were eating because that's what tasted good to them at the time. So of course this brings up another question, which is are we like that? Because we don't think we're like that. We tend to think that deliciousness is out to get us, and we have to kind of resist, that food is fuel, and that we can outsmart all this kind of machinery - bodily machinery, brain machinery - and the possibility is we're getting it all radically wrong. Shawn Stevenson: Yeah, man this is super interesting stuff. And you kind of highlighted- and the name of the book, 'The Dorito Effect' is fascinating in and of itself. But this big shift took place around the time that the Dorito was invented. So can you talk a little bit about that story? The kind of history of the Dorito? Mark Schatzker: Yeah, so have you seen the show Madmen? You know that show? Shawn Stevenson: Yeah. Mark Schatzker: Advertisers on Madison, Don Draper, exactly. Well there was a guy named Arch West who could have walked off the set of that show. He was a Madison Avenue ad guy in the 1950's. He worked on like Jell-O Pudding's account, Campbell Soup's, and he was invited to be the VP of Sales and Marketing for the Frito Company. So he moved his family to Dallas, and shortly after he got there, the Frito Company merged with the Lay's Chip Company, became Frito-Lay, a company we've all heard of. So shortly after that, Arch West takes his family on a trip up to California. Really interesting little side story, he goes out for his favorite lunch one day, which is prime rib, and on his way out of the restaurant, he meets the guy who started McDonald's. And they have this conversation- what was the McDonald's guy's name? For some reason I'm blanking. Shawn Stevenson: Kroc. Mark Schatzker: Ray Kroc, exactly. Meets Ray Kroc, Ray Kroc compliments his daughter's beautiful golden hair. Asks, "Have you ever eaten at my restaurant?" Turns out Arch West hasn't even heard of it because McDonald's hasn't gotten to Dallas yet. So these two titans of the food industry have this interaction and basically talk about hair and then go their separate ways, never to talk again. But the real important moment on that trip came a little while later, Arch West was driving south to San Diego, and he passed what he called a little Mexican shack. And he was the kind of guy who just had to stop, so he pulls in there, and he tastes for the first time a tortilla chip, and he's really taken by it. And he has this vision, he says- he thinks to himself, "Tortilla chips are going to be the next big thing for Frito-Lay." So he goes back to Dallas, he springs this idea on the corporate brass, and they just sort of look at him funny and they say, "Why would we sell tortilla chips when we already sell Fritos which are kind of the same thing? Just more like a different shape happening." But Arch West is so convinced about the future of tortilla chips that he actually funnels discretionary funds to an off-site facility where he figures out how to make them, he comes up with a name which in a very bastardized pigeon Spanish means 'little pieces of gold,' and he re-pitches it, and he says, "Gentlemen, I give you Doritos." And he gets the green light. And I know what you're thinking, this is the moment everything changed, Americans started gorging on junk food, and we started getting bigger, but that's not when things changed because what happened next is really interesting. The original Doritos bonked. Nobody got them. In the southwest, where there was like a Hispanic kind of Mexican cultural influence, people knew. Yeah, tortilla chips are great. You can dip them in bean dip, dip them in salsa. But everyone else said, "This snack sounds Mexican but it doesn't taste Mexican." So Arch West has to go back in front of the people he had essentially lied to, the people who green-lit this snack that was failing, and they say, "What are you going to do about Doritos?" And this is when everything really did change because he said, "Let's make them taste like taco." And one of his fellow executives started ribbing at him and said, "Our Yankee friend from the north doesn't know the difference between a thing and a flavor." And it was a really good comment because right up until about that time, different things had different flavors. Like if you wanted to experience the flavor of fried chicken, you had to eat fried chicken. And if you wanted to experience the flavor of cherry or the authentic flavor of strawberry, you had to eat those things. We had some fake flavors back then like really fake tasting strawberry chewing gum, or really fake tasting strawberry ice cream, but flavors were really in the domain of nature up until that point. But Arch West knew that there was new technology, which let you impose flavor on anything you wanted. For the first time in the history of our species, we could make a triangular piece of fried cornmeal have the zingy tang of a taco, the same savory depth. It doesn't taste exactly like a taco, but it tastes kind of like a taco, and you put one in your mouth, and you want to keep eating. And just think about that for a moment because we're talking about something that on the surface we're all a little bit frightened of, right? Carbs, fat, salt. The original Doritos had all that stuff, nobody wanted them. Then they dust on this sprinkling of flavored chemicals, and a snack that no one wants becomes a snack that people literally cannot stop eating. So that really tightly illustrates the power of flavor technology to make us eat stuff. Shawn Stevenson: Man, that is so fascinating. So what did they use? What was this technology that allowed scientists to start to extract and understand these different flavors? Mark Schatzker: A very important device called a gaschromatograph. And a gaschromatograph is really good at analyzing substances that exist in minute amounts. So before the gaschromatograph, science knew an awful lot about food. We knew about vitamins, we knew about minerals, we knew about carbs, we knew about the omega-3s and the omega-6s, but we didn't know about flavor because flavor exists in food in tiny, tiny quantities. Like we're talking parts per million, parts per billion, even parts per trillion. Then in the mid-1950's, a device called the gaschromatograph is suddenly available, and what that does is it volatizes the chemicals in food and puts them through a coil, and in the coil they kind of arrange into all their constituent parts. So they just start marching out the other end one by one so you can split them all up, and you can capture them, and then you can go analyze them using technology called mass spectronomy. And then you know what the flavor chemical is and it's really easy to go, "Hey, why don't we just make these ourselves?" And that's what happened. Shawn Stevenson: Right. Man, when reading your book, I started to realize all of the different flavors- because this is so fascinating if people get this. There's a difference between a thing and a flavor, and that just really struck me because we've become a culture that's just immersed in things that aren't actually supposed to taste like it does, tasting like something else. So what I mean by that is- Mark Schatzker: We've never questioned it, right? We've never thought, "Orange Fanta tastes like an orange. Is it supposed to be that way?" We grew up with it so it seems normal, but it's actually really recent. Shawn Stevenson: Yeah, so fascinating. I'm thinking about like all of these different things, these 'fruit' snacks, fruit punch. Mark Schatzker: Yeah. Shawn Stevenson: 0% fruit in it. And even the name itself, like what is a fruit punch? It's like a punch in the face. Like it's a punch in your mouth that you just can't even process. It's just so fascinating that this was like something that somebody came up with, and it started around this time with the Dorito. Mark Schatzker: Yeah, exactly. Shawn Stevenson: Well simultaneously, you also mentioned that- because we're looking at this paradigm with food now. We have this increase in flavor with these things that are things that aren't necessarily supposed to have this particular flavor. But then we have natural foods that start to have a reduction in flavor. So let's talk about that. Why is that happening? Mark Schatzker: Exactly. This is the other side of the flavor coin, and in some ways even more alarming. This is actually the question I originally started to ask because one of the things I noticed when I was doing my steak book is that the steak you go and buy at the supermarket doesn't have a lot of flavor. And then you go to Argentina and you taste one of these grass-fed Argentine steaks and you're like, "Oh my God, what was that?" And then I started to notice everything's getting blander. The people I would talk to would say, "Well this is high output agriculture. We keep growing more of everything." So if you look, for example, at the Dorito itself, the corn that it was made from in the mid-1960's was already very different from the corn that went into the original Fritos in the 1930's because our yields of corn have just been getting bigger, and bigger, and bigger. We grow more corn on the same acre of land than- I mean it's astounding how much more we grow. If you look at things like tomatoes and strawberries, we grow like an order of magnitude more. We're getting ten times as much fruit from the same acre of land as we used to. Now on the one hand, this is a really good news story because we have more mouths to feed and we have less farmland than we did 100 years ago. So if it was not for these agricultural innovations, there would be a lot of hungry, and even dead people. So it's really good that we cranked up our ability to produce food. However, the question we never ask is has this come at a cost? And we started to get a whiff of that in the late 1990's. There was a study that came out in the British Journal of Nutrition that found that actually whole foods, which are called whole, they're wholesome, are getting less wholesome. It found that there was less vitamins, less minerals than before. It was alarming that it caught the attention of a biochemist at the University of Texas. His name was Don Davis, and he thought, "This doesn't sound great," but he wasn't sure if they did the study right. So he did an extremely rigorous study looking at like fifty garden fruits and vegetables, analyzing them for vitamin content, for mineral content; 1950's varieties versus 1999's varieties. And what he found is that on average there's an across the board decline that these foods are- he calls it the Dilution Effect. There's just not as many vitamins and minerals in them as there used to be which is alarming. I mean on a very basic sense, these are whole foods, this is the stuff that's supposed to be good for you, it's getting less good for you. It seems intuitive, right? Because you think, "Well of course, I put a strawberry in my mouth, it tastes like cardboard. I put one of those tomatoes in my mouth, we know how terrible tomatoes taste." But what the really interesting link that I was looking for, and wanted to forge, and which brought me to an absolutely fascinating body of science is the link between flavor and nutrition because this is something we never talk about. Because here's the thing, all those vitamins that Don Davis was studying, they don't have any flavor. This is why nutritionists have avoided flavor from the get-go, because they don't taste like anything. Vitamin C is the only thing that has any flavor and it tastes a little bit sour. Once I got into the animal science, and oddly into the science of tomato flavor, that the curtain was pulled back and I realized there's this absolutely fundamental connection between the flavor of the food that we eat and the nutritional content. Shawn Stevenson: Man, that's exactly what I wanted to talk about today. And you state in the book that essentially our food-related problems are due to a largescale flavor disorder, right? We've got this simultaneously happening. Real natural foods, fruits and vegetables, their flavor is being reduced. So I want to talk about that first, the actual flavor itself. You gave the example of chicken in the book. And also at the same time, this increase in processed food having so much more flavor that's just kind of- you have no chance against it. Both of these things are happening at the same time, and wonder why people aren't eating more whole natural foods. So let's talk a little bit about the flavor itself of natural foods being reduced. Mark Schatzker: Yeah, so let's take the example of a tomato. There was a guy who has been working on this for years at the University of Florida, his name is Harry Klee, and he was initially tasked in the late eighties by Monsanto to produce a genetically modified tomato because everybody in the tomato industry- everyone knew tomatoes taste really bland, what can we do about it? They all thought it was because tomatoes are picked green, and then they're kind of like stored in a warehouse, and then when they want to send them to a supermarket they just fog them with ethylene gas, which is like a ripening hormone. Turns the tomatoes red, you go to the supermarket, tomato looks red, you take it home, you slice it, and it tastes totally bland. They all thought, "If we can just slow down the ripening process, we can get the tomatoes to ripen halfway on the vine, then we stick them in a box, ship them to the supermarket, and then they kind of ripen along the way, and they'll be ready to go and awesome. So that's what Harry Klee did. He developed one of the first GMO tomatoes, which was essentially programmed to ripen slowly. It worked, the tomato took like three weeks to ripen instead of a week, and it didn't taste any better. And at this point, Harry Klee decided he'd had enough of industry, he got a job with the University of Florida, and literally dedicated the rest of his life to trying to unravel the mystery of tomato flavor, because it's a mystery we all know. Most tomatoes taste terrible, but then like in July or August, you get an heirloom tomato, and you put a slice in your mouth, and it's just like this flavor symphony is raging in your head. So what Harry Klee found is that tomatoes have essentially forgotten how to be flavorful. They don't have the genetic ability to be flavorful because we've been breeding them for what we call agronomic traits. We want our tomatoes- we want a lot of them, we want them to have a good shelf life, and we want them plants to be disease resistant. So these are the traits that we keep selecting for, and what's happened is kind of a reverse evolution. When you don't select a trait, you lose it. It's the same reason we lost our tail. It's reverse evolutionary pressure. And over the decades after all this aggressive tomato breeding of not choosing flavor, we've lost flavor. You can take a modern tomato, it doesn't matter how you grow it. It can be in your backyard, organic, you can sing it lullabies, it will not be flavorful. So this is the story of so much of the food we grow because all we care about is quantity and price. We want more of it, we want it to be cheaper. Nobody ever sits down and tastes it and goes, "Is this a better tomato? Is this a better carrot? Is this a better cucumber?" And yet we all know it because so much of this food is just underwhelming. So you make a salad, and you're dumping Ranch dressing over it, you're putting croutons and bacon bits, you're doing anything to just make it taste good because it's so insanely bland. And yet we also know in the back of our heads, it doesn't really have to be this way. Because some of us have been lucky enough, you might travel to Greece or Italy where they grow some really wonderful produce, and you have a very simple salad with just a little bit of olive oil and a squeeze of lemon and some sea salt, and it's like a revelation. You're just like, "This is the best salad I've ever had," and they haven't done anything to it. That salad recipe wouldn't work here because our greens- especially like supermarket January greens are so bland. Maybe you can pull that off at a farmer's market. So, so much of the whole foods that we grow, meat as well, chicken is the best example. The chicken we grow- so chicken in the 1940's, the chicken that our grandparents or great-grandparents would have eaten would have been around sixteen weeks old when it was at the supermarket. The chicken we eat today is six weeks old, so it's essentially a giant baby. Chickens are ultra-fast growing, they're incredibly cheap, and they're incredibly bland. It is so difficult to make chicken flavorful. We brine it, we put dry rubs on it, we make sauces, we do anything we can to make it just taste like something. Shawn Stevenson: So, so fascinating. You know, one of the things that also jumped out in the book is this concept- you shared the story of Debby in the book, of incentive salience. And we're looking at this paradigm where we've got all these artificial flavors, and actually looking at brain imaging scans, and seeing what's going on in the brain. Because the reason I want to talk about this before we get into some of the other things is a little bit to do with food addiction. Because I thought you talked about this so elegantly, and even kind of funny in the book, and just kind of bringing this right to the forefront of what's going on for us when we're experiencing this thing. So can you talk a little bit about that story? Mark Schatzker: Yeah, absolutely. I got very interested in this idea because one of the things I resist, as I've told you, my interest in all this sprang because I really love to eat, I travel different parts of the world, sometimes we go to fancy restaurants, sometimes we just eat by the side of the road. But I really became interested in this idea of flavor and deliciousness. And what a lot of people say is that the problem with our food culture is that we're surrounded by too much delicious food. And I'm sitting there going like, "I don't really buy it." I mean if you're eating donuts, and drinking cola, and eating potato chips, it's like a pop song. It gets you in the moment, but nobody would ever say this is really great, right? It's not like Beethoven's Fifth, or something truly memorable. So I got interested in this idea of food addiction, and most people think - especially the morbidly obese - they think that their problem is that they just like food too much and they don't have the good sense to stop, when you and I have the good sense to stop. But of course that doesn't really make any sense because these people want to stop, and they're in the grip of something they can't control. So when they look at- when they take people who have let's say a problematic relationship with food, they have difficulty controlling what they eat, and they put them in a brain scanner, what they find is that if they show them let's say a picture of a milkshake, they experience this burst of desire for it that's just like off the charts. They'll see that picture of a milkshake, and they'll want it a lot more than you or I will want it, but then they'll actually taste it, and their enjoyment of it will be equal to what you or I might like, or even below. So they're in this crazy relationship where their problem is that they want food a lot, but they don't actually like it anymore. They might even like it less. And I think that tells us something really interesting, is that something that we've done with our food has really distorted our relationship with food. We're making food more cravable, but we're not actually making it taste any better. And I think we all know this to some degree when it comes to things like Doritos or potato chips, we've all been there. You go to a Superbowl party and there's the big bowl, and you're like, "No, I'm not going to have any." And then you're like, "Maybe I'll have one." And you have one, and would you say that was the most delicious thing you ever ate in your life? Not a chance. But what you experience more than anything is just like your hand is going back to the bowl, it's like you're trying to pull it back. There's this compulsive element. And that's this experience we've created, is that we've made food in a way more compulsive, but not really that delicious. I think if you asked a lot of people what their most delicious food experiences would be, it wouldn't be that stuff. It would be like a pie that their grandmother made them, or like a chicken that their mom roasted, or an incredible steak like the one I had in Argentina. Shawn Stevenson: Yeah. Mark Schatzker: Or an amazing tomato, or a peach, think of how good peaches are in the summer. You know, you bite into that thing, and the juice is running down your chin. I mean that's a food moment. Shawn Stevenson: Yeah, man and that's what life is too. It's kind of like this is- like music is the soundtrack to our lives, food is as well in a way, you know? And it speaks this language. And again, you just kind of detail it in the book, and also specifically sweet foods speak a very strong language to not just humans but a lot of other animals as well, but specifically for human physiology. So I want to talk about our hardwiring to desire sweet. I've talked- I did an episode, and I'll put that in the show notes, The History of Sugar. We went back and literally looked at when it was extracted from sugar cane, and how it kind of found its way into Europe, and the whole story behind it. But then we got into present day because now we can test things, and we can see- we can give rats in a lab the opportunity to choose cocaine or artificial sweetener, and you see them get addicted to the artificial sweetener rather than the cocaine. It's so crazy to see this. What is it about sugar that makes us so- kind of we're hardwired to eat it. Let's talk about that. Mark Schatzker: Yeah, well you know, as soon as we come out, as soon as we're born, sugar makes us smile, sugar is something we want. It's a source of energy. And obviously sugar has come under a lot of scrutiny in the last several years, everybody is talking about it. I'm not in full agreement- because here's what I would add. It's actually not sugar that we want. It's sweet foods that have a sweet taste, but also something else, and this is why I think the flavor industry is so interesting. Because if you look at all the sugary sodas in the supermarket, just imagine them in your brain all the sugary sodas next to one another. They are all nutritionally speaking the same thing; sugar and water. There might be like a little caffeine, there's caramel color, but they're basically sugar water with some carbonation. It's the flavor that makes them delicious. It's the flavor that makes Dr. Pepper taste different from Ginger Ale, taste different from Coca Cola, taste different from Fanta. Right? It's the flavoring. Would any of us drink those if not for the flavoring? I don't think anybody would. I've given my kids sugar water and they're like, "No thanks, it doesn't taste very good." It's the flavoring. It plays such a big role. So the sugar, that's the macronutrient that's implicated in things like insulin resistance and obesity. I don't dispute that once that sugar gets in your stomach it's doing stuff, but what we have to ask is why is it getting there? And we are hyper-incentivizing it by making it taste more delicious than it deserves to be. Shawn Stevenson: Very interesting. And also- so this is a good place to kind of segue into we're looking for something else. It's not just the sugar, but the sugar can indicate that there is some other potential value in the food, you know? For example, eating a properly grown peach, like you talked about. We're going to get some other things packaged into that. So let's shift gears and talk about how flavors can actually indicate potentially nutrition. Mark Schatzker: Yes, so let's just think for a moment about flavor, and how does flavor work? We rarely pause to think. We're all in search of deliciousness, we all want our dinner to be as delicious as possible. Even when you're on a diet, you run out and buy like the diet book that has fifty-five can't miss recipes. We all want food to be delicious. Well what is this experience of deliciousness? It's two things. It's the taste that you experience on your tongue with your taste buds; sweet, salty, bitter, sour, umami. A lot of us kind of know that. We feel like the tongue is doing all the work. But there's this other thing happening called retronasal olfaction. Big word, but what it really means is back of the nose smelling. So what happens when you eat, let's say as you're bringing that pizza close to your mouth, you first sniff it with your nose, it smells like pizza. But then when you start to bite it, those pizza vapors go in the back of your throat, and then up that tube that connects to your nose and stimulates your smell receptors. So what nobody realizes is that as they eat food, as they chew food, they're actually smelling it, and it's a different kind of smelling. It's received by a different part of the brain, and that's what gives food its nuance, its rich flavor, its character. Maybe it makes the most sense to people once they realize that when they have a cold, food doesn't have any flavor, and it's because this retronasal olfaction has gotten shut off. So it turns out the DNA to make that equipment, it's the biggest chapter in the manual to make you. If you think that your DNA is like this instruction manual, the biggest chapter is on how to make your nose. So obviously it's there for a really important reason. What's it doing there? Why do we have this- it's a gaschromatograph only it's way more sensitive and way faster than the ones the scientists use. So why is it there? Well I got in touch with a scientist at Utah State University named Fred Provenza who has the most fascinating body of research that he's done on sheep and goats, and he asked the same question. What is flavor there for? And he would do these crazy experiments where he'd take two groups of sheep, and he would make them deficient in something important. So phosphorus is an example. Phosphorus is a mineral, if you don't get enough phosphorus, you're going to die. It's essential. He would make these sheep deficient in phosphorus, they start doing crazy things. They start eating dirt, they start trying to drink the urine of sheep in the other pen that aren't deficient in phosphorus. They are like totally, totally desperate. And then one day, he takes one of these groups of sheep, and he puts a- what he calls a ruminal infusion, so he sticks a tube down their throat, and he blasts in some phosphorus, and at the same time they eat this feed that tastes like coconut. And then the next day, he puts some water in their stomach, and he gives them feed that tastes like maple. And then so there's this association going on. The phosphorus itself doesn't taste like coconut, but it's associated with the flavor of coconut. And then after a bunch of days of doing this, these sheep- he makes them deficient again, and what do they do? They go, "I want to eat the coconut feed." It's like they've realized this is where the phosphorus. Now what a lot of people say is, "Oh but how do we know that sheep just don't like the flavor of coconut?" Well, he took that other group of sheep, and he reversed it, and he paired the phosphorus with maple, and those sheep would go, "Hey, I want to eat maple when I'm phosphorus deficient. I don't want to eat coconut." So that's what I was talking about earlier about flavor feedback. This is why we have this elaborate, amazing chemical sensing apparatus right in the middle of our face that is taking chemical readings of the food that we're eating all the time, because the flavor of food is a guide to the nutrition that's in it. Now for the big question, right? Maybe sheep do that, maybe- who knows? Nature is a different place. Can humans do that? Well, it turns out the history books are pretty revealing. I started to look at the history of British sailors who would get scurvy, because I wondered when British sailors got scurvy, would they sit around craving oranges? It makes sense, right? You'd think that would be a good thing to do. Well, I talked to a plant scientist and he said, "No, of course not." And I said, "Well how do we know?" And he said, "Well if they did do that, we'd know about it." And I thought, "Man, he's probably right, but I'd better check anyway." It turns out they did. Scurvy is the most- I mean it was a devastating disease. Their gums would swell up, their hair would fall out, wounds that had been healed for fifty years would open up and start bleeding again. It was awful, but it was characterized by something they called scorbutic nostalgia. So it just wasn't a physical ailment, it was a mental one, and one of the symptoms of scorbutic nostalgia was just an overpowering craving for fruits and vegetables. They would look into the ocean as they sailed over a coral reef, and they'd see all the coral reef heads, and in their minds those would transform into cabbages because they were craving foods that had vitamin C. There's a chaplain who recorded a ship- it was out adrift in the Pacific for weeks. Like they were throwing twenty dead bodies overboard a day, so many people were dying of scurvy. They finally hobble into this island called Juan Fernandez, the middle of the Pacific, and what do they do? You'd think they'd go and like trap a deer or something, or eat some groundhogs. They start eating moss. They start ripping wild turnips out of the ground, and they wrote about how delicious they tasted. So for them, there really looks like there was this intuitive knowledge of, "I want to eat the food that I need." Even more interestingly, is that tomato scientist I told you about earlier, Harry Klee, one of the things he did was map out- he figured out what the flavors are in tomatoes that we like. Turns out there's about twenty-six of these flavor compounds that really drive our liking of tomatoes. So Harry has this idea that, "Hey, if I can figure out how the tomato makes flavor, then I can start to target those genes and breed for a more flavorful tomato." Well when he traces back the metabolic pathway that a tomato uses to make flavor, what does he find? All twenty-six of those flavor compounds are synthesized from an essential nutrient; carotenoids, omega-3s, vitamins. So it's like the flavor of a tomato is a big chemical sign saying, "There's good stuff inside here." Shawn Stevenson: Wow, that's so, so powerful. So food with flavor- so flavors are really essentially like labels. They're like labels indicating what you're going to get. And we kind of distorted it by creating all these artificial flavors, but it's still a guide for us. Mark Schatzker: Well and think of how beautifully this worked in nature. Because we live- before we developed the gaschromatograph, when we lived in a more natural setting, we had this major problem because we needed fuel. We needed carbs, we needed fat, but we also needed all these micronutrients. And you just can't go pick these things off a shelf in nature. Any food you eat will have all of these things in varying amounts. So our brains over millions and millions of years of evolution had to get good at figuring it out, and it was a system that worked brilliantly for so long. We would not be here obviously if we were incapable of feeding ourselves. But because these things are connected to pleasure and the drive to eat, that you can instantly see as soon as you start to mess with that, weird things are going to happen. Shawn Stevenson: Right. It's just so Captain Obvious. And so the next thing I want to cover is- we talked about sweet, but there are some other flavors that we kind of have categorized today that I want to dive into. But first we're going to take a quick break. So sit tight, we'll be right back. Alright we are back and we're talking to the author of 'The Dorito Effect,' Mark Schatzker. And this is just- I've said 'fascinating' probably ten times already. Super fascinating, and just looking at what's really going on behind the scenes with flavor. And as I said before the break, flavors are like labels, and this is one of the things he really makes a clear case for in the book. So you mentioned umami, right? So we've got sweet, we've got salty, sour. Let's talk about what that is. So can you describe for everybody what it is and how does it play into our desires for flavor? Mark Schatzker: So umami is a Japanese word that gets variously translated as savoriness or deliciousness. It is the- if you think of something like soy sauce, soy sauce tastes salty but it also has this deeper, rounder, richer flavor. That's umami. And it's something that we weren't aware of for a long time, they got onto it in Asia before we did. That's not to say it wasn't in our food, it's just not something we knew about. There's a lot of umami, for example, in parmesan cheese. Umami, it is believed is there, the reason we like it is because it's an indicator of protein. So protein is something we need, protein is an enormously important building block for our bodies. So umami is particularly interesting because it's also one of the things we put in those Doritos, because you put umami on a tortilla chip, and it suddenly has that captivating depth, that savoriness. You add some flavors, some tangy flavors, and all of a sudden you've got something that tastes pretty good. Shawn Stevenson: So this is something- also MSG, right? Monosodium glutamate. Mark Schatzker: Yes, MSG is the same thing. Now everybody says- there's a lot of conspiracy theories about MSG that it causes cancer, or that it's like a brain toxin, and then there's a lot of pushback enough that says it's perfectly natural, MSG is found in all sorts of foods. It is found in all sorts of foods, but the point I would make is what's unnatural about it is turning it into a powder that you can then just start throwing on all sorts of junk food to make it more delicious. Because eating really is our number one problem. It's gotten to the point that eating has become essentially toxic because so many of us are eating so much. So that's where I would raise the alarm. All these things I'm talking about are natural chemicals. All these flavors that we're talking about are natural chemicals, but we're using them in unnatural ways. Shawn Stevenson: Can you talk about your experience- this was at Green Canyon Ecology Center, and there was a substance that you tasted there. Is it a sucrum? Mark Schatzker: Sucram, yeah sucram. Sucram is what's called a palatant. It's something they put in pig feed to make pigs eat more feed. Because farmers really want- so this is where livestock becomes interesting. Farmers want their animals to essentially be the opposite of what we want for humans. We want humans to live long and be lean. Farmers want their critters to grow as fast as possible, to be fat, and to kill them as young as possible, because that's where they make their money. They're not evil people, but this is what the market demands, and that's what they do. Well if you can twig on any little trick as a farmer that would get your critters to eat faster, you'll do it. So industry has developed what they call palatants, which are chemicals you can put in animal feed that will make the animals eat more and eat faster. So they use sucram to put it in pig feed so they can wean piglets at an earlier age, and they give their- kind of soybean and corn feed, it gives it the flavor of mother's milk. There's sweeteners in there, and there's like vanilla, and these little piggies gobble it all up. Shawn Stevenson: Sucram. It just sounds cram. Cram. Mark Schatzker: I mean it's funny because like you add just like a little cup of it to an entire ton of feed, you mix it up in this industrial thing. We had some- I was at Utah State, and there was a little pinhole hole in the bag. We were just like- all of a sudden we were like, "What's going on? Everything smells so sweet." And it was just like the tiniest amount just absolutely overwhelmed us. That's how powerful this stuff is. Shawn Stevenson: That's crazy, and a lot of folks, we just don't have any idea about that. You know? Just the smallest amount can just become overwhelming to our senses, you know? Mark Schatzker: Yeah, well you put it in your mouth and it tastes good. Shawn Stevenson: Yeah. Mark Schatzker: And you know, we've been talking an awful lot about junk food, things like candy obviously uses flavor. There's no fruit in a fruit flavored candy. Sodas. But a lot of this is in what we think of as being real food. If you look at- I've got kids, so one of the things that parents really love to buy for their kids are those little yogurt sticks. It's like a tube of yogurt. There is like pictures of fruit all over those things. You look at that thing and you're like, "Oh there's going to be like strawberries, and blackberries, and raspberries in there." There is no fruit in some of those things. There's just coloring, flavoring, and sugar. And yet it tastes like fruit. Nobody would ever know otherwise. Shawn Stevenson: That is so crazy. Reminds me of the snack pack when I was a kid. You get the pudding. Mark Schatzker: Yeah. Shawn Stevenson: Man, this is nuts, man. And it's just- again, it's not really real food. And I'm thinking about the display and the marketing. In some of this stuff it just really kind of seems unethical because the average person is not going to consider- like I remember when I realized that something said 0% fruit, and I was getting Hawaiian Punch, for example. I would get it for years, and I thought, "Oh, like I'm getting fruit juice." And it just like clicked, it took like several years of drinking this stuff before I realized. So it's crazy, crazy stuff. So let's talk a little bit about- so going back and looking at this kind of olfactory sense. When you said earlier about when you might have a cold, and you're eating food, and how it tastes different. I want folks to really think about that, and just how much our sense of smell plays a role in our ability to distinguish these different foods and the value there might be in it, right? I see people in the studio here shaking their heads. This is so fascinating. But with that said, babies. Right? Babies. You have some- because if we were left to our own devices, could we figure this stuff out without all of the stuff we've been hit with. And you have a study in here, Clara Davis study, and you showed in your book how babies can naturally kind of start picking the foods that they actually need. Can you talk about that? Mark Schatzker: Yeah, Clara Davis, what a fascinating woman. So this was in the late 1920's, and this was at a particularly interesting time because science was just starting to figure out what the essential vitamins were. And of course, no sooner do we figure out what the vitamins are, then panic sets in and everyone is like, "I'm not getting enough vitamins," and there's this real concern that babies and picky eaters aren't getting enough vitamins. It got to the point where pediatricians would tell mothers to starve their children until they eat their broccoli. Shawn Stevenson: By the way, I've experienced that. Mark Schatzker: You've been there. Shawn Stevenson: Like, "Sit there, you're going to eat it." Yeah. Mark Schatzker: We're still in therapy, aren't we? So Clara Davis decided to test this. She thought, "What is a baby's intuitive sense?" If you just leave a baby up to its own devices, what's it actually going to eat? So she took- I think it was like forty babies. These were like babies from women who'd died, or from prostitutes, or widows, situations where a baby really couldn't be cared for. And they were raised in a hospital setting, and every day they were given a choice of food. It was just presented as a choice. There was no, "You should eat this," "You shouldn't eat that," there was salt- there wasn't salt on anything, they could do that themselves. And she just wanted to see what their choices would be, and did they only go for the oatmeal and the bananas and the orange juice, for example? What she found is that these babies did an extraordinarily good job of feeding themselves. They had some bizarre meals, like they would have like orange juice and liver for dinner, for example. But they did a really good job. They came in sick and under-nourished, and by the end of the study, one of her colleagues commented on what a fine looking group of children this was. And perhaps the most interesting case in that experiment was a baby who came in with Rickets, which is a deficiency of vitamin- oh God, I'm blanking. Shawn Stevenson: Vitamin D. Mark Schatzker: Vitamin D. And this baby was sick. One of the cures, the known cures, back then for rickets was cod liver oil. Everybody hates cod liver oil. I mean even people who's never tasted it have heard of cod liver oil. I mean just the sound of it, like oh my God, who would squeeze oil from a bunch of cod livers and feed it to children? Sounds so horrible, right? Well this baby has rickets. Clara Davis gives it a little cup of cod liver oil. No- like nothing, it's just there. "Drink it if you want." The baby sniffs it, the baby starts drinking it. The baby drank cod liver oil until its rickets went away, then it never touched another drop. Shawn Stevenson: Just blows my mind. If we have the opportunity- this is one of the greatest things, and I haven't really talked about this before on the show, but one of the biggest things behind what I'm doing is to try to help usher us back to a place where we can just listen to our bodies. And the craziest thing is like you would think we'd be able to do it, like we're in our bodies all the time, but our senses are so overwhelmed with all these different things that we just don't become aware of. But here's what I've experienced. When I shifted over and began to eat predominantly real food, my body just knows like for pretty much all winter, I really didn't want any fruit. I ate a lot of avocados, this kind of thing, but just recently like when I was on vacation, I just wanted grapes. I just wanted to eat them. And I'm not even like a big grape fan, but I just allowed myself to eat them. My body wanted something. Sometimes I might get a meal and I've got a plate, and the entree looks fantastic, but I just want to eat the vegetables, and I just allow my body to eat the thing that it really wants a lot of the time. But you know, with humans and with our structure and we've got families, there's a lot of different things where we're going to have things that are kind of set in stone of what you're going to eat. But the more that we can kind of get back to that place, and reset our palate, which is what I want to talk about next. Like what are- you've got three rules of flavor. So first of all, let's talk about those, and then let's talk about what are some of the things that we can do to help to take back control of our flavor system. Mark Schatzker: Okay, so what I want- the simple take home message from all this is that the one thing- we all know this, but we all pretend it's not true. We are flavor craving creatures. We love the taste of food, we love it at least three times a day. You're not going to get rid of that. Only the most strong-willed among us can deny themselves the pleasure food. The rest of us are in its grip, and for a reason. Because this is the second rule; in nature, there is an intimate connection between flavor and nutrition. The flavors that we crave, the flavors that bring us delight, bring us more than delight. They bring us the nutrients that we need. We know that flavor can build food. You take something like a peach that can be incredibly delicious, that isn't chock full of calories. You just couldn't eat a basket of peaches the way you could a basket- like a whole bucket of junk food. But we also know that with flavor technology, we slice this intimate relationship between flavor and nutrients right down the middle, and we're only left with the pleasure, none of the nutrition. So I want everyone to think about that, and then you think, "Well what do we do to try and fix things?" It's very simple. You avoid the stuff that's been engineered to be delicious. You do that by looking at the ingredient label and if you see the words 'artificial flavors,' or 'natural flavors.' You just need to know, somebody in a lab sat there and tried to figure out how to make this as delicious as possible. The second thing you do is try- it's not just about eating real food. It's about eating the most delicious real food that you can find. It's really hard to eat a bland tomato. It's really not hard to eat a flavorful, amazing tomato. And I think when you look at the parts of the world that are much leaner than us, you look at countries like Japan, and Italy, and France, they're not all on diets, they're not obsessed with whether it's carbs that are killing them. They eat for pleasure, and they eat real food, and I think if we all did that, there'd be a lot more joy in our lives, and we'd all be a lot healthier. Shawn Stevenson: Said it perfectly. So a couple quick things, last question for you. What is the model that you're here to set with the way that you live your life personally? What's the model you're here to set for other people? Mark Schatzker: The model is to eat real food and enjoy it. I actually have several of the hallmark symptoms of food addiction; I'm obsessed with food, I think about food, I crave food, I travel to strange places to eat food, but I have a very positive relationship with food. We're supposed to love food, and I think if you can find a way to get that pleasure from real food, it's nourishing but it's just also such a wonderful aspect of your life. Shawn Stevenson: I love it. Thank you. Thank you so much for sharing that. Also, can you let everybody know where to pick up your phenomenal book? And I highly- by the way, guys, this is a must for your library. So get this book like yesterday. Let everybody know where they can find your book. Mark Schatzker: It's in bookstores, it's on www.Amazon.com. I hope everybody enjoys it as much as you did. Shawn Stevenson: Definitely. This is one of my favorite books from this past year for sure. It's been out for a little while, but it's getting this resurgence, and it's such an important conversation. This conversation talking about flavor, and this is like the left out- I went to a traditional university, I had my nutrition classes, and we didn't talk about flavor. Like this just was not a thing. Mark Schatzker: No, it's not. And this is why it's interesting. Like you said, this book came out a few years ago, I'm still getting emails like every day from people who are discovering it. Because I don't think this is- this isn't just a fad. Flavor is a part of your life. I mean unless you like literally chop the nose off your face, it's a part of your life, and we have to understand it and celebrate it. Shawn Stevenson: Absolutely. Absolutely. This is going to really stand the test of time. A lot of folks are going to be reading this for many years to come, and I'm just very grateful for you putting it together. I know that it took a lot of research and articulation. It was a joy to read, it's funny, it's informative, and man, just thank you so much. Mark Schatzker: Thank you very much. I really enjoyed the chat. Shawn Stevenson: Awesome. Are you on social? Can people follow you anywhere? Mark Schatzker: Yeah, I'm on Twitter @MarkSchatzker. I'm on Facebook, I'm on Instagram. Shawn Stevenson: Perfect. So we'll put all that in the show notes. Mark Schatzker, everybody. Thank you so much for joining us. Mark Schatzker: Thank you so much. Shawn Stevenson: Everybody, thank you so much for tuning into the show today. I hope you got a lot of value out of this. I'm not kidding, this is one of my favorite books. I couldn't put it down. I couldn't put it down. I was supposed to be on vacation, but I just kept my kind of analytical mind on for the first part of my vacation until I got through it. Alright? And then I kind of shifted gears and got into some other stuff. But it's just utterly fascinating. This is a huge component of food that we just don't talk about. And I love his point- and this is really the secret. When people hear, "I've got to have restriction in order for me to be healthy." "I have to struggle." "It's going to be a challenge." We have all this psychological turmoil thinking that eating real food, and having a healthy approach to our food and our nutrition has to be suffering, and you're going to be missing out on something. The key is to eat delicious real food. That's the key. There's no deprivation, there's no restriction, there's no feeling of, "I'm being-" of not-enoughness. If you eat real delicious food, it just transforms your life, you know? So that's really kind of the thing that I live by. I love the food that I eat. I eat real food the vast majority of my diet, but it just tastes amazing. It's like the best food I've ever eaten all the time, and we can all have access to this. But it's making those choices, experimenting, figuring out what things really work for you. And this trickles down into what we do in our lives, and what's going on in our communities, you know? Where are we sourcing our food from? Rather than buying the kind of commercial greenhouse grown whatever tomatoes, maybe you're going to the local farmer's market and getting the heirloom tomatoes, or whatever the case might be. Giving yourself these different experiences, because sometimes you're going to have something and you're like, "Oh this is what it's supposed to taste like." You know? And that changes you forever. And so also, I highly recommend to - like he mentioned - going different places and experiencing different cultures. Even if you could do that in a small way. You know, trying different things in different cultures, that's what really was one of the bridges for me changing my palate was Kenyan food, you know? My wife being from Kenya, having this opportunity to go to their house to have dinner one day, and true story with my wife being from Kenya, going over to have dinner that first time at her parents' house, man I'll tell you. This is a true story, I was scared. I was like, "I don't know what they're going to have. Is it going to be alligator?" Just these kinds of really just messed up thoughts I was having. So I decided I'm going to eat three bowls of cereal before I go. I'm going to get full and I'll be like, "I just ate, I'll just have a little bit." But when I got there, and I just allowed myself to try some different foods, some traditional Kenyan foods, it changed me. It changed me. I'd never had flavor experiences like that in my life, and it really opened me up to try new things. Until that point, there were a lot of foods that were just around my normal day-to-day life that I'd never experienced, like avocado. You know? That was something that I would see, but it was just kind of in the background. You know? But they really introduced it to me in the form and fashion and packaging up of that food with everything else. And so have the audacity to try new things, support your local farmer's market, CSAs. Try the same food but try different versions of it, you know? Go for those heirloom varieties so you can get more connected to this process. Alright? One other thing that he talked about is the opposite is something that's preached, and I really want to help us to get over this, is believing that this concept- and I heard him say this and mention this in his work as well, if it tastes good, spit it out. This idea that food isn't supposed to taste good, that we have this battle going on, waging a war against food and deliciousness. I think it's very counterproductive. And the more that we can embrace the fact that food is supposed to taste good, but now we're going to shift over and we're going to eat real delicious foods. It's really going to guide us in having the health, and the vitality, and the physical fitness that we really want, alright? So we all have the opportunity, and I'm so grateful for you tuning into this episode today. If you got a lot of value out of this, make sure to share it out with your friends on social media family. Tag me of course, and make sure to pick up 'The Dorito Effect.' Alright? It's an amazing book that's really going to help to open up your mind to that flavor flav, alright? So check it out, alright? I appreciate you so much. We've got some incredible guests coming up, incredible show topics, so make sure to stay tuned. Take care, have an amazing day, and I'll talk with you soon. And for more after the show, make sure to head over to www.TheModelHealthShow.com. That's where you can find all of the show notes, you can find transcriptions, videos for each episode, and if you've got a comment you can leave me a comment there as well. And please make sure to head over to iTunes and leave us a rating to let everybody know that the show is awesome, and I appreciate that so much. And take care, I promise to keep giving you more powerful, empowering, great content to help you transform your life. Thanks for tuning in.

Maximize Your Energy

Get the Free Checklist: “5 Keys That Could Radically Improve Your Energy Levels and Quality of Life”

Share Your Voice

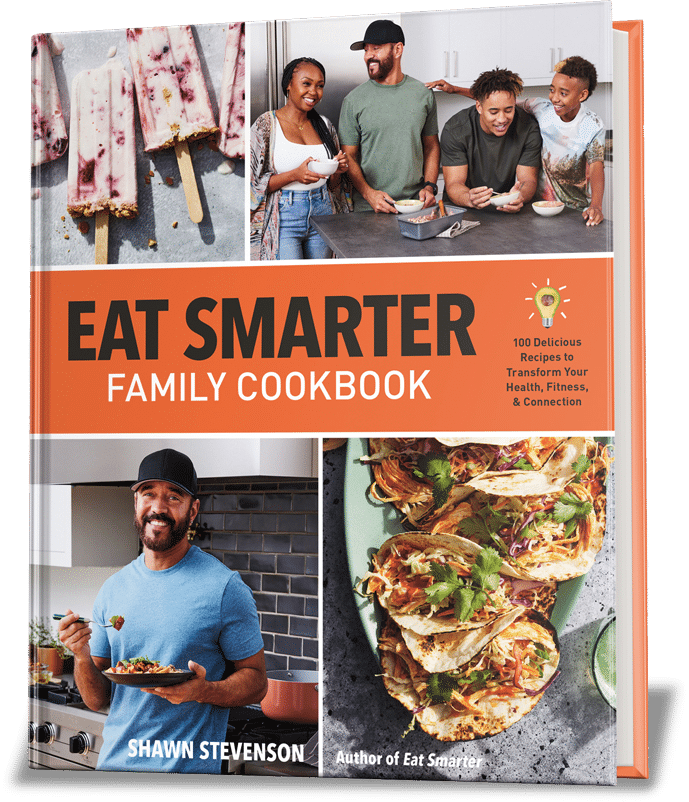

HEALTHY MEALS EVERYONE WILL LOVE

The Greatest Gift You Can Give Your Family is Health

When you gather your family around the table to share nutritious food, you’re not only spending quality time with them - you’re setting them up for success in all areas of their lives.

The Eat Smarter Family Cookbook is filled with 100 delicious recipes, plus the latest science to support the mental, physical and social health of your loved ones.

HI Shawn,

I’m truly grateful for your life changing show. I have learned so much from your podcast and book as well as your guests books. I’m looking to learn more about vitamins and minerals and was wondering if you have any recommendations?

Thanks,

Mike

Hey Mike,

Thank you for your kind comments! For micronutrient resources, Dr. Chris Masterjohn has great sources that I would recommend you dive into!